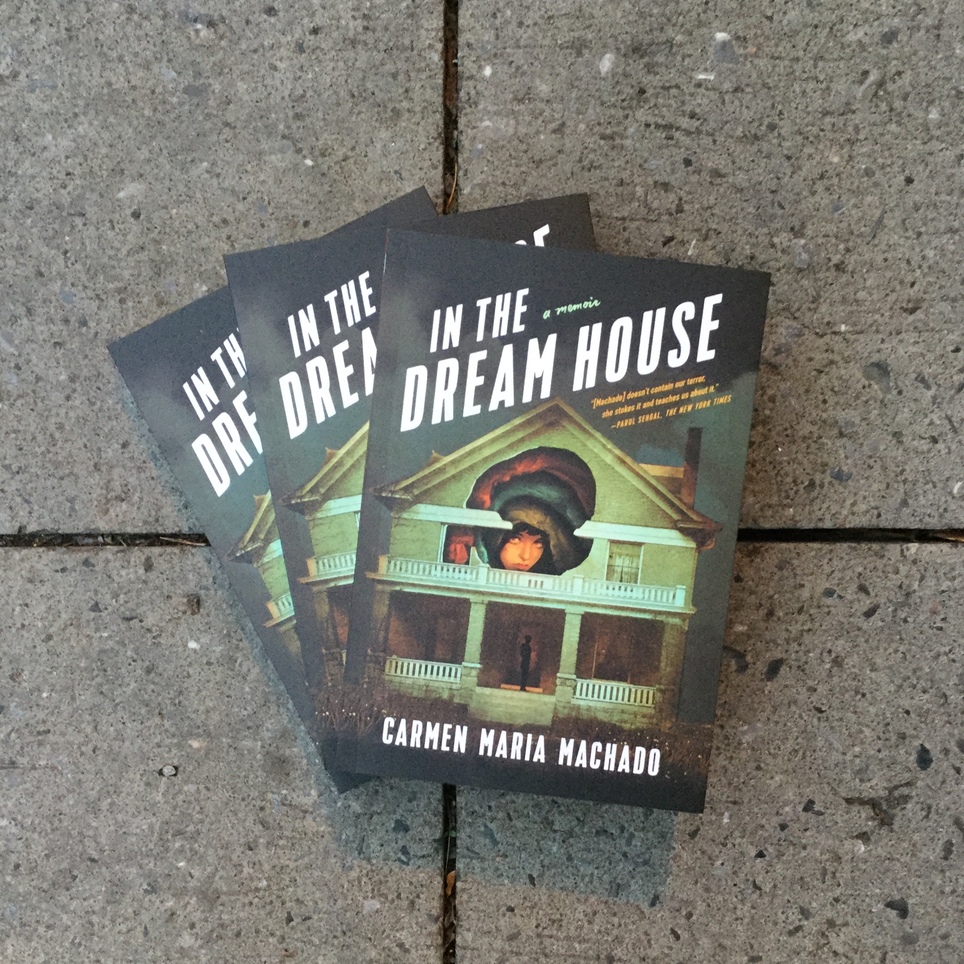

Carmen Maria Machado In The Dreamhouse

- Welcome to the House of Machado. Proceed directly into the forbidden room; enjoy the view as the floor gives way. Her new book, “In the Dream House,” is a memoir of her frightening and abusive.

- An Amazon Best Book of November 2019: The shattering memoir In the Dream House from Carmen Maria Machado (Her Body and Other Parties) pivots around the small house in Bloomington, Indiana, that Machado’s girlfriend moves into shortly after they meet. This cozy domestic abode soon turns into a harrowing locus of emotional abuse.

- In the Dream House is Carmen Maria Machado’s engrossing and wildly innovative account of a relationship gone bad, and a bold dissection of the mechanisms and cultural representations of psychological abuse.

- In her new memoir of life in a psychologically abusive relationship, In the Dream House, Carmen Machado forgoes traditional structure, eliminating standard narrative and refusing to reduce the story to the confines of a single spacetime in order to convey this temporal dislocation. After all, a story that only meets the requirements of a.

- Carmen Maria Machado In The Dream House Review

- In The Dreamhouse Carmen Maria Machado Deutsch

- Carmen Maria Machado In The Dreamhouse Pdf

- Carmen Maria Machado In The Dreamhouse

- Carmen Maria Machado

- Carmen Machado

Carmen Maria Machado In The Dream House Review

Format: 264 pp., hardcover; Size: 6×9″; Price: $26; Jacket Art: Alex Eckman-Lawn Publisher: Graywolf Number of Dream Houses in The Dream House: 144; Opening Dedication: If you need this book, it is for you; Another book by the author: Her Body and Other Parties; Representative Passage: Dream House as the Wrong Lesson: “ When MGM made the Academy Award-winning version of Gaslight in 1944, they didn’t just remake it. They bought the rights to the 1940 film ‘burned the negative and set out to destroy all existing prints.’ they didn’t succeed, of course—the first film survived. You can still see it. But how strange, how weirdly on the nose. They didn’t just want to reimagine the film; they wanted to eliminate the evidence of the first, as though it had never existed at all.”

In The Dreamhouse Carmen Maria Machado Deutsch

Central Question: What is the correlation between the architecture of a house and the infrastructure of traumatic experience?

Last Updated on February 10, 2020, by eNotes Editorial. I database for mac. Word Count: 1163. In the Dream House is a cross-genre text that incorporates elements of memoir and nonfiction.In it, Carmen Maria Machado.

Carmen Maria Machado In The Dreamhouse Pdf

Sufferers of abuse live according to the logic of a fragmented reality, one that adheres to different rules from linear experience: times contorts, introducing the possibility of winding, repetitive, and cyclical temporality. In her new memoir of life in a psychologically abusive relationship, In the Dream House, Carmen Machado forgoes traditional structure, eliminating standard narrative and refusing to reduce the story to the confines of a single spacetime in order to convey this temporal dislocation. After all, a story that only meets the requirements of a coherent narrative—touching the flagposts of a beginning, middle, and end—would be inept to the task of conveying the true experience of Machado’s past self. Machado charts this erased territory and crafts a retelling of her psychologically abusive relationship with a former romantic partner, a young unnamed woman. The psychological violence employs volatile mechanics: cycles of manipulation and humiliation, narcissistic, and egomaniacal tactics designed to magnify shame and fracture self-love. The two aspiring young writers first meet at a diner in Iowa City, but as their relationship progresses, the dynamic becomes confusing to Machado’s past self. Her confusion stems from the fact that there has been so little language ascribed to romantic abuse in queer relationships. She navigates this often ignored dynamic by re-configuring the memoir form—and her understanding of her own past—so that it adheres to an architecture more accurately attuned to her lived experience.

In The Dream House finds Machado inventing new formal tricks in service to her past self—the memoir’s “you”—and creates a narrative structure that allows her to connect her past and present. We learn about Machado’s splitting in “Dream House as an Exercise in Point of View.” “You were not always just a you,”she remembers. “I was whole—a symbiotic relationship between my best and worst parts—and then, in one sense of the definition, I was cleaved: a neat lop that took first person—that assured confident woman, the girl detective, the adventurer—away from second, who was always anxious and vibrating like a too-small breed of dog.” It’s through these types of experiments that Machado is able to play with a diversity of literary forms, and interrogate her experience through a variety of approaches. Instead of rejecting the categorical labels of genre, Machado embraces them—all of them. The story of her ill-fated relationship—the titular Dream House—shapeshifts as Machado tries to understand her own experience. We encounter it in myriad forms as the book is broken up into genre-specific sections: Dream House as Accident, Dream House as Stoner Comedy, Dream House as Soap Opera, Dream House as Comedy of Errors, Dream House as Queer Villany, Dream House as Star-Crossed Lovers, Dream House as Sci-Fi Thriller. The sections feel scrambled in their arrangement, as if anything could come next; yet the memoir as a whole comes together in a way that tracks intuitively and emotionally.

There are essays that reach into the crevices of fairy tales, film, philosophy, myth, origin, or common belief. In “Dream House as 9 Thorton Square,”Machado investigates the origin of the word “gaslight,” tracing the phrase from the lamp itself, to the Ingrid Bergman movie, to the insidious dynamic of manipulation and denial that leaves its victims questioning their own sanity. “Bergman’s Paula is a terrible double-edged tumble: as she becomes convinced she is forgetful, fragile, and then insane her instability increases. Everything she is, is unmade by her psychological violence: she is radiant, then hysterical, than utterly haunted,” Machado writes. “By the end she is a mere husk, floating around her opulent London residence like a specter.” The essay banks up against more directly personal sections, where the author once again enters the cage of her own confusion, using the facts to explore the compromised reality of her own experience. At one point, she puzzles over the discrepancy between her partner’s words and her actions: “She says she wants to keep you safe. She says she wants to grow old with you. She says she thinks you’re beautiful. She says she thinks you’re sexy. Sometimes when you look at your phone, she has sent you something weirdly ambiguous, and there is a kick of anxiety between your lungs. Sometimes, when you catch her looking at you, you feel like the most scrutinized person in the world.” The memoir’s critical and memoiristic segments rely on one another to draw out the narrative as a whole, which they are able to do not despite their different shapes but because of them. Navigating their arrangement feels frantic and grasping, and the story emerges through its own inability to settle or sit still. Some sections are only a single sentence, while others run for pages. In the Dream House flourishes in its hybridity like a live amorphous goo safe in its petri dish, cellularly shifting so radically that it appears fluid.

The writing feels most tender when Machado addresses her past self in the second person in the sections that follow. You, she calls herself whenever she returns to a scene of a love crime, you walk… you are calm now… you love… The construct is one of clean dissociation, enabling the harsh scenes or memories to be summoned only through the present tense, literally depicting the way that ones painful, confusing or conflicting memories imprint themselves on the present. In these passages, the narrator is constrained by her sensory experience, depersonalized, watching herself exist outside of herself. In a section titled “Dream House as Chekov’s Trigger,” Machado writes, “You slide down to the floor of the bathtub, sobbing, and she walks away. You sit there until the water hitting your body is icy. After a few minutes like that, you reach over and turn the handle to off, shivering. She comes into the bathroom again. When she gets close to you, reaches towards you, you realize she is naked. “ Why are you crying?” She asks in a voice so sweet your voice breaks open like a peach.”

As a reader, I was seduced by what I initially thought was the musicality of these parts, the percussive you / you / you like a bass drum, which had the impact of a hypnosis instructional guiding me through Machado’s waking life dream. But as I read on I realized that the technique allowed me to reverberate alongside the text and its writer in a rare way. Machado grants us access to the way she both speaks and interacts to her subconscious memories, letting us watch her ego-less, excuseless, unapologetic self do something it never thought it might be able to do—exist. She lets herself be confused and pulled in various directions, confronting her own credibility, embracing paradox, watching herself as she gets swung back and forth between love and hurt, love and hurt, love and hurt, often the effect of the swinging proving to be a glueing one, leaving her stuck in a freeze. The sections highlighted the nonverbal underbelly of abuse with such an ease that anyone who has been subjected to psychological trauma will, while reading, easily taste the ghost scent of that freeze.

For me, the relief in witnessing these relivings comes from a writer finally giving something amorphous—the impacts of gaslighting and abuse—a shape. In writing In The Dream House, Machado has confirmed a huge something for a lot for people who, like her, might doubt that abuse ever occurred in the first place. She shows us that we’re not insane. That not only our experience, but the way in which that experience is organized and assembled, is a true and viable reality, as real as anything else, as real of a reality as anybody else’s.

Carmen Maria Machado depicts the complexity and surreptitious truth of the abuse of queer women through the mosaic portraiture of her own past self in her memoir “In the Dream House.” Machado, the author of the short story collection “Her Body and Other Parties” and a finalist for the National Book Award, employs original methods of storytelling and teaching in her latest work, recounting her past through a string of vignettes all written within the confines of various narrative tropes, such as haunted house or choose your own adventure. These vignettes, read on their own, range from masterfully crafted, poetic lines of introspection to descriptions of Machado’s past relationship with abuse.

By chronicling her own experience with abuse, Machado informs the history, or lack thereof, in literature about abuse in queer relationships. The point isn’t to document the history of the abusers and the abused, as Machado points out, “The abused woman has been certainly been around as long as human beings have been capable of psychological manipulation and interpersonal violence.” Machado keeps returning to this central idea within the memoir: Stories of abused women have been silenced, and even more so, the stories of abused queer women have barely had a chance to be told.

Carmen Maria Machado In The Dreamhouse

Machado’s fragmentation of her own story into many storytelling archetypes seems ambitious and unexpected for a book centered around such a serious topic. Ripping apart and piecing together the narrative actually reflects how Machado was feeling during her time “at the Dream House,” a phrase Machado uses to reference the times she was in her abusive relationship. She explains that during her time in the “Dream House,” she began to experiment with fragmentation in her writing: “Every narrative you write is smashed into pieces and shoved into a constraint,” she writes. This memoir has been split into dozens of different anecdotal stories told through many tones and styles, rather than focusing on on one linear narrative. Machado, employing this fragmentation, was able to portray simply through form how her ordeal in the “Dream House,” disrupted the way she thought. The stories, however, are not quite as fragmented as she describes. In fact, the stories blend together with beautiful synergy, completely separate in motive and form, but strung together narratively and emotionally.

Machado vacillates between first person and second person perspectives. These alterations are not at random: Clearly the two beings, the “I” of her present and the “you” of her past, are distinctly different characters in the narrative arc as a whole. One is within the circular devastation of the “Dream House,” and the other is finally outside of it reflecting back on the pained and suffering girl that is, for the purpose of the story, wholly different from Machado’s present self. This use of “you” even subconsciously, places the reader into Machado’s perspective in the 'Dream House.”

Carmen Maria Machado

There is a chapter entitled “‘Dream House’ as Choose Your Own Adventure®” where Machado places the choice of action on the reader. There are places in this chapter that the reader can’t reach by following the adventure set out by Machado, and they read like a variation of this: “You flipped here because you’re sick of the cycle. You wanted to get out. You’re smarter than me.” And toward the end of the chapter, the choices start narrowing down to one page, where the cycle of the adventure begins again, repeating until the reader is forced to read pages they shouldn’t read to break the cycle that Machado was trapped in. Somehow, Machado was able to use structure and form to convey a message that doesn’t translate without the experience itself. The idea that stories of abuse are circular and seemingly unending doesn’t necessarily attach to the reader until they are making the choices and they get lost in this loop themselves. Machado masterfully plays with structure to convey wordless emotions that carry much more weight than can be merely described.

Carmen Machado

Machado slips between the voices of numerous narrative tropes so effortlessly, conveying an overall tone of dissonance that, done poorly, could have been misinterpreted as incoherent but is actually artistically masterful. Machado is able to resuscitate the buried history of abuse in queer relationships with a mix of her own story and the stories of past battered queer women whose stories were suppressed, untold, or trapped in a faraway 'Dream House.”